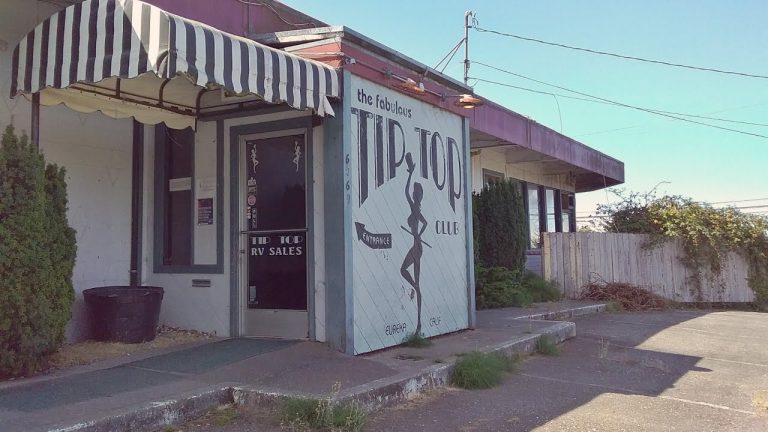

If you’ve run packs from the Bay or done any clandestine dealings in Humboldt before 2018 it’s more than likely at one time or another those transactions took place in the parking lot of the Tip Top, the only strip club in the Emerald Triangle and unofficial community hub of The Hill—the nickname affectionately given to the lush mountains of NorCal where growing cannabis is prevalent.

The standalone building was a known destination for lonely farmers and trimmers alike, a veritable trading post pre-legalization, and a hidden treasure trove for dancers. Perched on a bluff off the 101 and Salmon Creek Road in Eureka, the big glass windows tell a clever story to unsuspecting passersby, but only the real ones know what’s actually gone down between those four walls.

The Early Days

When the Tip Top opened in 1997 the original owner, Tom, known to all as T. Great Razooly, was able to maneuver around zoning and licensing laws by designating the club as an RV sales office. According to veteran dancer Jasmine, “all the girls working there were technically RV salespeople and there was one little toy RV that sat on Tom’s desk.” Eventually granted a proper business license, the club changed hands in the early 2000’s—purchased by none other than a former dancer named Sassy.

Back then, clientele ranged from “rednecks to hippies, to hippie-rednecks”, dancer Miraya recalls. Born and raised in Humboldt, Miraya is the daughter and granddaughter of cannabis growers on her dad’s side and millworkers on her mom’s side. She saw the first major industrial shift—from logging to growing—in real time. “Growing up there was tension, loggers didn’t like weed growers, but they had no choice once the lumber and fishing industries died. If they wanted to stay in Humboldt they had to do something.”

She laughs, “I remember camo being the factor that brought them together. Camouflage clothing was the one thing they shared.”

“There Was So Much Money”

The Tip Top earned its covert reputation as a hidden gem for easy money among the underground stripper community, but the customer demographic was a culture shock for dancers coming from urban places like San Diego, like Autumn, or Atlanta, like Honey. The latter came to Humboldt on a tip from a mutual friend in Vegas. According to Honey, “The clientele was weird. They were hippies and they were all kinda dirty. No one was ultra-attractive – they all looked like farmers. But I sat at the bar and every single guy in there asked me for a dance that first night. I decided to stay and made $4,200 in a couple days.”

Autumn started working at the Tip Top after coming up from San Diego to live with her boyfriend who worked at a property on Titlow Hill. “I’d been dancing for years, but had never seen money or customers like this. I was a little reluctant at first, but my boyfriend at the time kept telling me how much money he’d see thrown around there. I remember working on a weekday around Halloween and this guy, I’ll never forget him, his name was Blake. I think he had just done a big deal or something because he had stack after stack and was raining hundred dollar bills on me and Honey and some of the other girls. I made over $6,000 that night. Blake, if you’re out there, please know we still talk about you to this day.”

Honey corroborates the story, “That was one of my most fond memories at the Tip Top.”

While the majority of customers were farmers, not all farmers were of the hippie-redneck variety. There were pockets of Hmongs, a subset of indigenous Chinese, and a smattering of various eastern European outfits. According to Jasmine, one Bulgarian grower from SoHum, “threw $1,274 for a single song on my stage. It was my best stage set ever.” Cinnamon echoes a similar experience, “long story short I was very short on money this Tuesday night. Sure enough, one grower—classic dready with a trimmer girl on each arm—comes in and rains hundred dollar bills on me. I danced to Led Zeppelin’s ‘You Shook Me’ and this guy lost it. Paid my rent, car payment, and bills in one song”.

Do You Accept Weed?

It wasn’t just cash being thrown around; many dancers say they were tipped and paid in flower.

“Regular customers knew that I would take weed as payment. That was actually much better for us because people who deal in weed pay more. If they owe you $100 they’re going to give you half an ounce or an ounce. Back then, weed was much more valuable, we were paying about $100 for a quarter,” Miraya says. She reminisces about legacy strains like Trainwreck, GDP, White Widow, White Rhino, Orange Crush, and “later on, Purple Urkle. It became what everybody wanted, what everybody was looking for and [it] smelled so good when it was burning and growing. You could smell it from a mile away.”

Jasmine says she was tipped a pound on stage once, and Honey was given a half pound at a private party which she took home with her to Los Angeles on the Amtrak and sold piecemeal to her friends, netting her about $5,000. Autumn also said she was once tipped an entire pound, but after taking it home and attempting to wash it in hopes of making ice water hash to press into rosin, she realized it had already been run through a dry sift tumbler. “There were no trichomes on that bud. It was literal grass clippings”.

One of Honey’s regulars even helped finance the pole studio her and another dancer, Tiger Lily, started together. “I had a grower, he was my regular, and every time he came down from the hill he’d come see me. I told him we were starting a studio and when I told him the name, Body High, he was so happy it had to do with weed. I told him each pole was about $1,000 and it was going to have to come out of our pockets. He came and saw me every week for five weeks and gave me $1,000 every time”.

Lonely Hearts Club

While the Tip Top facilitated their fair share of debaucherous sprees like bachelor parties and birthdays, most customers came for one of two reasons: to suss out potential buyers or, more often, to enjoy a temporary respite from the loneliness of The Hill. “They were just chill, lonely growers,” Jasmine explains, “a lot of times we would get guys [who’d say], ‘I haven’t even seen a woman in months!’ And they had more money than they knew what to do with. I remember I’d do multiple-hour dances with this one grower who would come in and nap. We would literally just sleep back there.”

Isolation was one of the biggest occupational hazards for growers and trimmers sequestered in the hills. “The workers were desperate for attention. The bosses were a little more picky, but they all had an excess of money and would give [their] right arm just to see some boobs and have a real conversation with a girl,” says Autumn. “They mostly complained about work. We were like their little bikini-clad therapists.”

She continues, “I had this one regular and he would come in and we’d talk about music and just life in general the whole entire time. He’d bring me his newest strains to try. I never did any real dancing for him, but he paid me like I did.”

The End of an Era

The old saying “All good things must come to an end” sadly rings true for the glory days of the Tip Top and Humboldt as a whole. Miraya laments, “I was there during what you would call [the] peak of legacy weed culture. I left in 2014-2015, right when they were beginning to legalize in other states. Real weed culture completely face-planted and Humboldt was not the same anymore. Everything that was iconic and notorious happened before then.”

Between legalization and wildfires, the bygone days of grows run on blood, sweat, and tears are a distant memory. Ghosts of yesteryear haunt the once-flush region, and the state of the current cannabis market mirrors the success (or lack thereof) of the club. “All the young girls come to the pole studio and they’re like ‘we wanna be strippers! We wanna go to the Tip Top’ and I feel bad for them because it’s not even worth dancing there anymore. They’re happy with one or two hundred dollars, they think that’s a lot of money,” Honey says with sadness in her voice.

The growers faced similar challenges. She continues, “Out of all the growers I met in Humboldt, I only know of two who still have farms.”

“My customer, the one who is the reason Body High exists, lost his farm and is a bartender on the Plaza now. He bought a house, but that’s really the only thing he has to show for all those years of growing.”