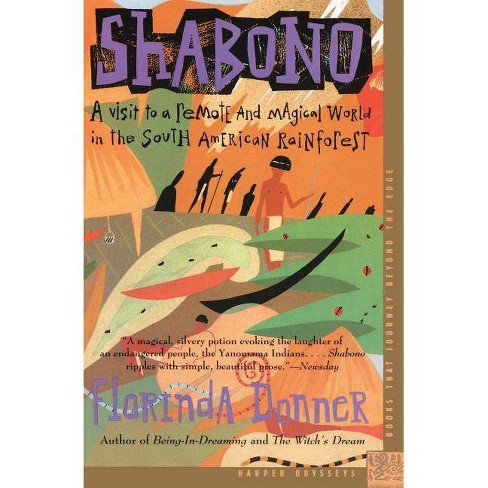

Browsing through an antique bookstore in Quito, I stumbled on a book called Shabono: A Visit to a Remote and Magical World in the South American Rain Forest, written by an anthropologist named Florinda Donner. Published in 1982, I expected it to be like most academic texts: interesting but long-winded and dusty. Instead, I got a gripping adventure that puts even Indiana Jones to shame.

The book opens with Donner, a German immigrant studying anthropology in California, feeling hopeless. She’s spent weeks on the border between Venezuela and Brazil shadowing Indigenous healers who refuse to reveal the secrets of their trade. Preparing to return to the U.S. empty-handed, she befriends a kind but crazy old woman who wants to introduce her to her village, located deep inside the rainforest. The woman dies on the journey, and when Donner arrives at the village, she joins a ceremony where she drinks banana soup seasoned with the woman’s ashes.

And that’s just the first couple chapters. Later, Donner experiences existential hallucinations after snuffing epená, a tryptamine derivative, and narrowly avoids getting kidnapped by another tribe.

The story of Shabono is so compelling I found it hard to believe it was true, which – it turns out – it wasn’t. While the book was praised for its writing, it was torn apart for lack of academic rigor. Some anthropologists believe Donner made everything up, claiming she never left the U.S. and plagiarized the account of a Brazilian woman who had once been held captive in the same region of the Amazon.

As shocked as I was to learn all this, the rabbit hole proved to go much, much deeper.

It’s hard to separate the story of Florinda Donner from that of Carlos Castenada. Castenada, like Donner, was a California-based anthropologist accused of fabricating his studies on Indigenous healing. He claims to have met Don Juan Matus, the Yaqui sorcerer at the center of his bestselling 1968 book The Teachings of Don Juan, whilst waiting for a Greyhound bus in Arizona. Critics questioned Don Juan’s existence, and Castenada, who didn’t like being questioned, offered no help in trying to locate him.

Although The Teachings was shunned in academic circles, it made a huge impact on the general population. Castenada’s recollections of inhaling the dust of psilocybin mushrooms and turning into a crow after smoking devil’s weed were required reading for anyone involved in the sex and drugs culture of the late 60s.

Though he might have been a lousy anthropologist, Castenada was a masterful storyteller who knew how to use his gift to bewitch those around him. Following the publication of his third Don Juan book, Castenada – by then a multimillionaire – purchased a two-story house in Los Angeles’ Westwood Village. This is where his personal writerly following would flourish into what some would now consider to have been a full-blown cult.

One of Castenada’s followers was Gloria Garvin, who sought him out after reading The Teachings under the influence of pumpkin pie laced with hashish.

“You have always been like a bird, like a little bird in a cage,” Garvin recalled Castenada telling her during their initial meeting. “You are wanting to fly, you’re ready, the door is open—but you’re just sitting there. I want to take you with me. I’ll help you soar. Nothing could stop you if you come with me.” Staying in touch, Castenada urged her to study anthropology at UCLA, his alma mater.

Also from UCLA Castenada recruited Florinda Donner, whom he helped write Shabono and The Witch’s Dream, among other books.

Castenada referred to his favorite followers as his “witches.” The witches lived with him at the Westwood compound and wore identical, short haircuts. They also claimed to have met the semi-fictional Don Juan. Witches recruited other witches at Castenada’s L. Ron Hubbard-inspired lectures and seminars on shamanism and human transcendence – preferably “women with a combination of brains and beauty and vulnerability,” according to ex-followers interviewed by Salon.

To become a real witch, they say, you had to sleep Castenada, who presented himself as celibate in public.

Testimony maintains Castenada’s following had all the characteristics of a cult. Followers were pressured into cutting off contact with their friends and family. Only Donner, who was considered Castenada’s intellectual and spiritual equal, remained in touch with her parents, albeit sporadically. After being separated from their loved ones, Castenada encouraged them to quit their jobs to make them financially dependent on him. Conformity was rewarded, mainly in the form of his sought-after affection.

Despite his obsession with immortality, Carlos Castenada died of liver cancer in April 1998. “Befitting of a man who made an esthetic out of mystery,” the New York Times reported when news of his death was made public after being withheld for weeks, “even his age is uncertain.”

As soon as one mystery left the world, another entered. A day after Castenada’s death, Donner and three other women close to Castenada disconnected their phones and seemingly vanished into thin air. Patricia Partin, Castenada’s adopted daughter, also went missing. Her abandoned Ford Escort was found in Death Valley. Years later, her remains were found there as well.

None of the disappearances were properly investigated by the LAPD, and so far, every citizen journalist and internet sleuth attempting to uncover the fate of the witches has run into a dead end.

Ex-followers believe the women took their own lives. In life, Castenada often talked about suicide, framing death as the gateway to a higher plain of existence. When his health began to decline, the witches reportedly acquired guns. Taisha Abelar, one of the witches who disappeared alongside Donner, started drinking, but told those around her she wasn’t “in any danger of becoming an alcoholic” because, Salon quotes, “I’m leaving.” Also per Salon, Castenada had told Partin to take her Ford Escort “and drive it as fast as you can into the desert” if “you ever need to rise to infinity.” Suspicious, but ultimately inconclusive.

Those who survived Castenada are convinced he genuinely believed everything he preached. As one ex-follower told Salon, “he became more and more hypnotized by his own reveries.”

It seems the witches did as well. In Shabono, Donner parades fiction as fact. While she may have originally tried to parade fiction for fact in order to obtain fame and fortune, readers get the stronger impression that, the further the young anthropologist ventured into her own fantasy world of life and death and drugs and mysticism, the harder it became for her to separate the real from the imagined.

At any rate, it’s a really, really well-written book.