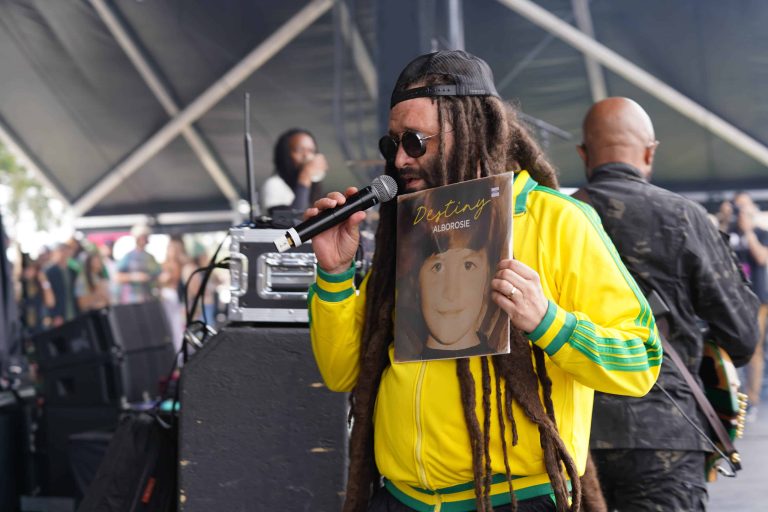

From his home country of Italy to his adopted home of Jamaica and across the globe at festivals everywhere, Alborosie has stood his ground as the anti-hero-cum-accidental-superstar of the international reggae scene. Recently released album Destiny —composed, recorded, produced, mixed, and mastered by Alborosie himself—affirms his status as one of reggae’s most prolific creators, and explores prickly themes many artists shy away from: the joke that is social media, the meaning of real reggae, and the unceremonious act of selling out for The Man. High Times sat down with the GRAMMY-nominated artist to discuss Destiny, weed, and everything in between.

The Subtle Art of Not Giving a Fuck

Alborosie has managed to shoot the precarious gap between the traditional Jamaican reggae of Burning Spear and Black Uhuru and the modern, Americanized version of artists like Stick Figure and SOJA, all while staying true to his roots and dogged life philosophy of “when everyone goes left, I go right.” It’s a bold and brave move in this musical economy where views translate to record deals and likes equal ticket sales, but he refuses play the game by their rules.

“It’s a social media time. It’s a time where the look is more important than the substance and I’m completely out of place. I don’t like to post every minute or show myself like that. It’s difficult right now for someone like me to fit into social media—the Instagram, the TikTok, the YouTube. I don’t like to feel the pressure of the views or the likes or the followers. There’s pressure, pressure, pressure, pressure and I say ‘You know what? Fuck the pressure.’”

His lead single “Viral” illustrates just that, picking apart the public gimmickry and image-obsessed cultural phenomenon in classic rub-a-dub style. Becoming an internationally recognized artist was never Alborosie’s primary goal, anyway. His move to Jamaica in 1999 was rooted by a need to find himself spiritually after being exposed to cannabis and the principles of Rastafari in Italy while touring as a young musician with his first band, Reggae National Tickets. It was during his many trips to and eventual permanent residency in Jamaica when his love affair with cannabis deepened and the true meaning of “one love, one heart, one destiny” was realized.

He elaborates, “It’s not like I moved to Jamaica because I wanted to be an artist. And actually when I moved to Jamaica, I didn’t want to be an artist anymore. I was done with the music. I said, ‘I’m moving to Jamaica to find myself spiritually, to find my place on this Earth, to find a place where I belong’ … I never wanted to be a big guy in the music world. I just wanted to follow my journey, my destiny.”

Spiritual Marijuana

The divine calling which led Alborosie to Jamaica also led to an intimate interconnectedness with God, music, and cannabis. But there’s one thing you need to know about Alborosie: don’t ask him to share his weed.

“I consider myself a ganja politician, because a lot of my songs them about ganja and the promotion of marijuana, spiritual marijuana … but I don’t share. I am against any sharing of [cannabis]. I don’t enjoy smoking with people, it’s very personal for me. I take two puff, leave it there, make some song. Drink a little orange juice, two puff, that’s it. Very cool and easy.”

He’s equally stringent with his acquisition of weed. It’s not an affront, he insists.

“I like to get what I know. That’s my rule. I need to feel your energy. I need to know you to smoke [your ganja], I need to know you to eat your food. I need to know where you come from—where is your spirit and how are you connected?

“I am a little afraid of your ganja, guys,” he jokes in reference to American weed, “In Jamaica I know where it comes from. I have my guy, Little John, that give me the weed from the backyard so I know the environment and I like that vibe … I don’t even know strains he just gives it to me in the package and I smoke it.”

Recording for Tomorrow, Writing for Today

Alborosie has built a quiet, content existence in Jamaica the past twenty years, give or take—his weed man is right down the block and his studio is right down the hall. So when asked what he did to ride out COVID, his answer was shockingly similar to that of us non-famous peasants: he simply stayed home (oh, and recorded music).

Though his album prior to Destiny, For The Culture, was released mid-2021 and partially recorded in the thick of quarantine, Alborosie doesn’t follow any strict timelines or record songs in chronological order, simply because he doesn’t have to. He even has skeletons of songs for his next album in his proverbial “song refrigerator” and records melodys or jots down ideas as the mood strikes.

“Because the studio is in my house, [recording] is just natural. I start on the computer, I play the guitar, I play the drums, I play the bass, write the lyrics. I have a different relationship with recording maybe compared to other artists because I am a recording engineer, mixing engineer, mastering engineer. So I basically can do everything myself.

“For me, it’s never like, ‘oh, I’m going to record an album’ … I just record every night. Then when it’s time to deliver the album I go in the fridge, open the fridge, get the ingredients, put them together in the microwave and then I have a finished record.”

His lyrics, however, are more timely.

“How can I write for today when my album is coming out in one year? Musically we can do anything we want to do, but in terms of lyrics we need to reflect the times were living in … you need to be relevant to today. Not yesterday, not tomorrow.”

Roots With Quality

Intentional, conscious, and always driven by real-life issues, Alborosie’s lyrics often speak of current events and societal injustices. Never simply “feel good” words, he keeps to true roots fashion and paints a picture of reality—even if it isn’t pretty. And while he plays the same festivals and tours the same cities as the ever-widening pool of American reggae artists he is often lumped in with, he feels the general lack of substance, lyrically, excludes them from the “reggae” label.

“‘Cali Reggae’ is not really reggae to me personally. Because my idea of reggae is from Jamaica—that rub-a-dub roughness, one drop, Rasta, cultural movement. When I see reggae, I see Rasta. It’s not a rule, it’s not a law, this is just what I believe. And because I am a reggae artist—a Rasta artist in Jamaica—there is no other reggae than this because of the roots and culture and foundation.”

He continues, “Everything else is just a mixture of genres and that is what the California version of reggae is. Musically, it has the same rules of reggae, but it’s not reggae. I respect everybody’s craft and people are entitled to do what they want to do, but I keep myself Rasta, revolutionary, Kingstonian reggae.”