By M.E. as told to Joe Delicado

M. E. doesn’t look like a Hollywood movie star. His face is too fat, his ears too large, his nose poorly shaped. And yet he would make a compelling appearance on screen. He has a distinctive style, a gruff but likeable voice, and he moves across a room as though he’s an actor in a movie of his own making. At the age of 32 he’s a veteran Hollywood marijuana dealer, cautious, sly and usually silent about his work. On the first day I met him at the Bel Air Sands Hotel he was wearing a white shirt, black leather tie, dark glasses and a Borsolino hat. Over coffee he talked about growing up in Southern California, and his initial forays into the dope trade as a high school student. He took me for a spin in his 76 Porsche. In Malibu we walked on the beach and had lunch at Geoffrey’s, a swank restaurant on the Pacific Coast Highway. Later that afternoon he took me to a secluded house along the shore and showed me half a dozen different varieties of marijuana, all of which he’d named after Hollywood movies: Burma Road, Citizen Kane, Treasure of Sierra Madre, Purple Rain, African Queen and Wizard of Oz. He rolled a joint. I turned on the tape recorder, sat back and listened while he talked about his adventures and observations as a dealer in the heart of movieland.

One Sunday night I was cruising along Sunset Boulevard, listening to Springsteen on the radio, just watching the world go by. A Mercedes Benz passed me in the left lane, then slowed down so that I could read the personalized license plate. It said “Movi Biz.” I followed behind for several blocks, and then suddenly I thought to myself, “This is my life. What else have I been doing for years but literally follow on the tail of the movie business.” That’s what it has felt like anyway, and I can’t honestly complain because I’ve made a decent living and I’ve had a chance to mix with celebrities, and some extraordinarily creative people, too. I’ve enjoyed serving as a drug dealer to the stars. I’ve had to put up with some prima donnas—more than a couple of actresses I’ve met have expected to be treated like queens. But they pay for it, and making two or three million dollars a year they can afford to. I’ve aIways had a sliding scale: you pay more if you live in the hills, and I don’t see anything wrong with charging a director or bankable star extra bucks for that pound of Jornia sinsemilla. Believe me, they get the best marijuana in the world—the stuff that the grower usually keeps in private reserve, and they get it all perfectly manicured, neatly packaged, sensitively wrapped. It’s the essence of designer drugs. Besides that, I always give a performance. I know the growers, know the history of the crop—where it was cultivated, when it was harvested, how it was cured—and I tell that story when I deliver the dope. It makes a difference knowing exactly what you are smoking. I make the season into a movie, but that’s exactly what you’ve got to do as a dealer in Hollywood. It’s what’s expected of you because Hollywood sees the world on screen. It sees life as a scenario. I’ve been following the Movi Biz so long that I’ve caught the disease. I see myself as an actor in a marijuana movie, and sometimes I’ve got to snap my fingers and tell myself that this isn’t a dream, that I’d better edit my fantasies or I’m the fall guy. But stopping the projector isn’t easy in Hollywood, especially with all that money and power and glamour. It’s incredibly seductive, and a perfect breeding ground for dreams.

My own fantasy was that I was going to make the big leap from marijuana dealer to movie mogul. In fact, early in my career as dealer I had the idea for a movie—a California marijuana movie. Not a documentary, not a Cheech and Chong comedy either, but a feature-length drama with all the essential ingredients and big stars too—Jack Nicholson, William Hurt, Jane Fonda. I didn’t have the plot all worked out, but I had reels and reels of images and scenes in my head, and I was certain that somebody would buy them and put them on screen.

Movies are a big part of my life. They always have been, ever since I was a kid, and they probably always will loom large in my field of vision. I guess that you could say that I’m addicted to the movies. I crave them, need them, desire them. Sitting in a dark theatre watching a picture is my favorite form of escape. I relax, open up, stretch my imagination. It’s like being born again and again and again.

The movies I like best are murder mysteries, detective stories, thrillers. I’ve never seen The Sound of Music, but what I do like I’ve seen over and over again so many times that I can recite the dialogue all the way through. My all-time favorites are mostly classics like Out of the Past with Robert Mitchum, The Big Sleep, The Maltese Falcon, To Have and to Have Not with Bogart and Bacall, Citizen Kane and The Third Man with Orson Welles, but I also like newer films, Scarface and The Godfather, of course, as well as The Sicilian Clan, The Big Chill, Gorky Park, Body Heat—you can see I’m a big William Hurt fan. I wanted to make a movie that would have the feel, the atmosphere, and the excitement too that those movies have generated in me.

I’ve been fortunate. Over the past dozen or so years I’ve gotten to know movie people—actors, directors, producers, writers, cameramen. I’ve got an inside track. So when I got my idea for a pot picture I began to knock on all those familiar doors, and to tell my story. Almost everything that I talked about had happened to me. I’ve grown pot, smuggled pot, sold pot; had encounters with cops, thieves, con artists, ex-cons, district attorneys, judges, customs agents, the DEA. So I took my own life and turned it into a movie. I had veterans of the trade spellbound right before my eyes. Some of the movie people I knew and trusted, and frankly admitted to them that all the material was autobiographical. But with others I was a lot more cautious. I didn’t see the need to confess felonies to everyone.

Right away I found out that I was naive. I didn’t realize how difficult it is to make a movie, especially a movie about drugs, and how many stumbling blocks there are. Hollywood is one of the richest drug capitals of the Western world. Hollywood loves its marijuana and its cocaine, but for obvious reasons it isn’t anxious to advertise that fact, or to make movies involving marijuana and cocaine. It comes too close to home. Sure there have been films in which drugs play a part. Jane Fonda and Dolly Parton smoke a joint in 9 to 5 and William Hurt snorts a few lines in The Big Chill. Drugs are a part of America—they’re as American as the World Series, as much a part of our lives as baseball and hot dogs. And wouldn’t that be a terrific movie to make, a movie about baseball and cocaine, with the snitch as the villain? But will Hollywood make that movie? Probably not. When it comes to illegal substances Hollywood is awfully cautious, and very much concerned to preserve its image.

One producer told me in no uncertain terms that there was an unwritten code at the studio where he worked. Number one, he said, you can’t show people doing drugs and deriving pleasure from them. You’re supposed to show the poor, pathetic junkie strung out, suffering miserably, and you’re supposed to show drug people as essentially evil types. Number two, you can’t show drug people getting away with it, because crime doesn’t pay. The growers and dealers can’t be shown making money and becoming successful. They have got to be caught and punished. This producer said that if he didn’t make a movie that fullfilled those two basic requirements he’d be in trouble. Sure he was making a million dollars a year, but he’d be unemployed. You learn right away that if you don’t play it by the rules, you’re expendable. If you don’t follow the code, church and civic leaders will be on your back. Gossip columnists will drop your name in bad company and pretty soon the corporation executives will be breathing down your neck. As you can guess, he turned down the idea.

Another producer told me that he had a reputation for being a head and that he was trying to shake that reputation, aiming for a newer, cleaner image in the ’80s. He claimed that he wanted to make a marijuana movie, but if he did, he said, everyone would assume that he was still smoking up a storm. So he couldn’t move on my project either. He had to make romantic comedies and love stories with happy endings.

Finally I did find a director who was hot on the idea of a California marijuana picture. Curiously, he didn’t smoke pot or snort coke. And he had even made an anti-drug propaganda film for high school students that was used by Ronald Reagan and the Republican Party in the last election. He was young and ambitious, this hustling director, and he thought that a marijuana movie with lots of sex and drugs and rock ‘n’ roll, and a bit of violence too, would make it big with the teenage market come summertime. He sat me down and tried to pump me to get all he could out of me: how marijuana was grown and how it was marketed, how much it cost and what kinds of people smoked it. He didn’t know anything about pot, or about human beings either because he’d spent his entire life thinking up plots and making up characters. I didn’t tell him anything about myself or my activities, just the kind of information anybody could get out of the library.

He insisted that the movie had to be a remake of an old movie. That’s the way Hollywood worked, he said. You took the plot from a movie that had been made in the ’30s or ’40s and you plugged in marijuana. Remakes were the key to success, he insisted. He chose the John Huston classic, The Treasure of the Sierra Madre with Humphrey Bogart. A terrific choice I thought, but by the time he was through with it, it was a joke, a travesty.

John Huston had been raped. The screenplay he wrote fullfilled all the requirements of the Hollywood drug code. At the end the marijuana is confiscated by the sheriff and burned. It goes up in smoke and nobody gets a chance to smoke it. All the characters are greedy, jealous, competitive, low-life types you wouldn’t want to know. The two men fight over the same woman. One of them kills the other. The other goes crazy. There was one stereotype after another. I tried to get him to recognize the distortions he was creating, but he wouldn’t see it. At the end of his story he had to bring in the Mafia. He couldn’t conceive of a drug film without the Mafia playing a big part. But that’s typical of Hollywood thinking. Mention drugs and they automatically think Mafia, greasy Italians smoking cigars and driving in black limousines.

From the start, this director had told me that he wanted to make a movie that showed drug people as losers, and that’s exactly what he did do. Funny thing—nobody wanted it, and he peddled it everywhere he could, from the big studios to the sleaziest of the independents. It was that bad, that offensive. Working with this director turned me off to the idea of making a marijuana movie. I got to a point where I wanted no movie made at all rather than having his rip-off put on the screen. The last day I saw him, he says, “Hey, can you lend me a hundred dollars?” You know, it hasn’t come back to me yet.

But some exciting things did happen to me when I tried to make a marijuana picture. I met lots of actors, directors and producers who wanted to buy pot, and who appreciate California sinsemilla, people who smoke it day in and day out and enjoy it, and at the same time are successful in their careers. Sure, I’ve met characters who have done so much coke that they’ve botched big pictures and blown big budgets, but.for the most part I came in contact with Hollywood people who get high and make good movies. They aren’t losers, not in the least, but big winners, and I became a winner too.

Dealing pot in Hollywood has been good to me. If I hadn’t become a marijuana salesman I’d be poor right now. I wouldn’t have my Porsche or this house. And marijuana has expanded my world. Without it I’d never have penetrated Hollywood. I’d never have gotten inside those mansions in Bel Air, Beverly Hills, and Malibu. Marijuana has been a kind of key, opening doors. It’s a rich atmosphere I’ve been able to move in and it’s gone to my head. I’ve gotten high just being among celebrities.

Sometimes I do some consulting. Two, maybe three times a year someone tells me that there’s a new marijuana screenplay making the rounds. My friends show me the screenplay, and ask “Is it accurate?” “What do you think?” All the screenplays are the same. They have the same basic plots and characters; they’re about losers. Crime never pays, and nobody ever enjoys drugs. One thing I’ve noticed is Hollywood people are under tremendous pressure, perhaps more pressure than marijuana growers or dealers. The grower or dealer has to beware of cops, thieves, pests, blights. The director or producer has tremendous competition from other producers and directors. They are always in fear of failure, of losing money, and making a flop. And actors—they are a world in and of themselves—such egos and such bundles of nerves. For them marijuana is medicine. It enables them to survive, to cope with all the tensions, the lights, the action, and the camera. Believe me, being in front of the camera can be as intense as being under the gun. You think there’s warfare in the dope fields and in the streets—hell, the warfare in Hollywood studios is much more intense.

My closest Hollywood friends tell me that by comparison with the work they do, my hands are clean. So many of them feel that they make dirty deals, prostitute themselves and their values, while the dope deals I do are clean and unadulterated. Maybe so. They seem to feel that they’re always having to make a pact with the devil, that for every decent film they have to make two empty films. They tell me they often have to trade off better judgments for bigger profits.

I’ve seen a lot. It’s been an education. I’ve watched the old rags-to-riches story unfold: guys working as messenger boys working their way up the ladder, becoming heads of studios and marrying actresses. But I’ve also seen the riches-to-rags story too: millionaire movie producers going under, Academy Award actors faltering in their careers and after a success or two, never making another big picture.

I’d still like to make a Hollywood movie about marijuana, something with style, humor, lots of action, and sympathetic characters. There might be a loser in the film, but it wouldn’t be about losers. Somebody might go to jail, but it would show that crime can, and in fact, does pay. It pays very well. And it would show what we all know to be true, that people get high and enjoy it. Maybe someday that’ll be possible. If so, I’d like to have a hand in it, maybe even do a little acting, maybe play the part of the marijuana dealer to the Hollywood stars. Right now I’ll go on dealing to Hollywood. This will be my ninth year. Sure there’s a risk, but so is making a picture. Sometimes I get scared and think about changing occupations. But I’m still here. There’s the money, of course, but there’s a big thrill too, especially in the fall, right after the California marijuana harvest when I arrive on doorsteps and in living rooms with pounds of the new crop, all pungent and fresh and waiting to be smoked.

I’ve brought pot to San Francisco, Seattle, Chicago and New York. New York is good. It’s one of the best, but nowhere do I get a warmer welcome than in Hollywood. Maybe because they’re under so much pressure they appreciate good marijuana. I’m treated like a hero, like a movie star you might say. Smoking dope, my friends tell me, keeps them honest in a dishonest world, and what could be more rewarding, more satisfying than that?

Except the parties. We do party a lot. And it’s exciting to be in one place with so many film people getting high together, eating, drinking, dancing, watching movies, and talking about movies, sitting in the sun and swimming in the backyard pool. I work hard and I like to play hard. I like my pleasures. As one director friend of mine says, “I’m a hedonist. While Rome bums, while this civilization of ours falls apart, I’m going to enjoy myself.”

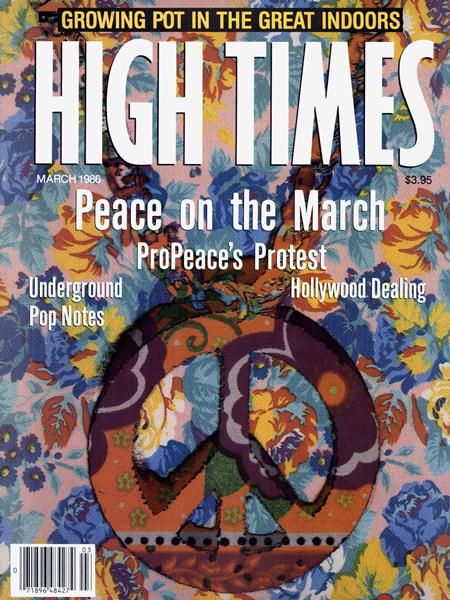

Read the full issue here.