I arrived in New York City in 1976 to become an actor. But after five years of pounding the pavement and a moderate amount of success, I considered my odds and decided that stardom wasn’t in my stars.

I landed in the fitness industry, which coincided with the fitness boom back when Jane Fonda was making videos and aerobic classes were the rage. I became the fitness director for New York Sports Clubs, a prominent chain of health clubs in the Northeast, and managed their exercise programs. But after eight years of professional exercise, I was cooked and profoundly unfulfilled.

Aerobics? This is my life?

As an actor, I’d waited tables on the Upper East Side and had become friends with a chef whom I worked alongside. His name was Peter Gorman, and he was an aspiring writer. Over time, his career had flourished. He ultimately was hired as an editor for High Times Magazine—which coincided with my disenchantment with the fitness industry.

Gorman needed a photographer. He had been assigned to write a feature on the great Comanche war chief Quanah Parker, who gained fame as a fearsome warrior and, following his surrender, as a successful cattleman and leader of his people. Parker was also known as the founder of the Native American Church, which was formed in the aftermath of the so-called Indian wars and uses the sacred peyote cactus in its ceremonies.

Gorman recommended me for the photography gig. So, in March of 1991,1 traveled to Oklahoma with him to do my first photo feature for High Times.

I never looked back. A couple years later, I was hired as an editor as well.

It certainly was never my ambition to become a top pot photographer but, as we all know, life takes us in unexpected directions. Truth be told, I’m not trained by any means. I didn’t even start taking photos until the age of 30. But I practiced like hell and always traveled with my camera. I shot people, rural scenes, cityscapes and still lifes, and I read articles about technique and studied what makes a successful shot in countless photography books. But taking thousands of photos prepared me for my career at High Times.

Having photos Updated in a national magazine is a major thrill, one that’s never worn off for me. I realized early on that in order to have my shots Updated, I had to become a dual threat: a writer/photographer.

From 1991 until I left High Times in 2017 as editor in chief, I became the most prolific contributor of writing and photography in the magazine’s history, traveling over a million miles on assignments.

During most of my career, pot was downright dangerous. Everyone was paranoid—and with good reason. Growers and dealers were being busted daily, and punishment could be incredibly severe. But these were the people I depended upon to cover the world of marijuana. I remain amazed at their courage and beyond grateful for them welcoming me into their lives.

No two people were more memorable or assisted me more than two Arizonans—Christie Bohling and Patrick Lange. I first encountered them at the inaugural meeting of the Hemp Industries Association, which took place in Paradise Valley, AZ, in late 1994. Christie and Patrick organized and spearheaded that conference.

It’s crucial to understand that the early activists of the modern hemp movement, more often than not, had heavy dealings with pot. The cash that funded those first hemp companies and ventures was usually pot money.

Christie had been a major-league smuggler in Arizona since the 1970s, the Queen Bee, a prime mover of thousands of pounds of Mexican marijuana. When she died in 2001, I wrote “The Ballad of Christie Bohling” for the magazine, a tribute in which I interviewed a number of her colleagues—even the Mexican “businessmen” themselves—who told tales of her sterling reputation.

She was a classy outlaw: reliable, honest and, most important, able to turn huge shipments of pot into money.

While Christie was brash and colorful, moving loads of pot with panache, showing the guys who the real boss was, Patrick was quiet and reserved, a man who rarely made eye contact—a cowboy type, taking things in, keeping judgments to himself.

Patrick had met Christie in the 1980s, and his intricate knowledge of the back roads and dusty, barely there trails of the Arizona desert and hills had served them well. However, when I met them, Patrick was in the midst of a five-year stretch of probation, after being betrayed by a police informer. So, at least for the time being, the couple had shifted their focus to hemp.

They cared deeply about the plant and both were students of America’s hidden hemp history. Together, they founded the Coalition of Hemp Activists (CHA), encouraging anyone who had interest in moving the issue forward to join them. The CHA even launched its own hemp clothing line.

One of its crowning achievements occurred in 1992, when the CHA staged and funded a formidable protest at the San Antonio Drug Summit, renting its own convention hall right next to the antidrug confab, where six world presidents were in attendance. Three thousand members of the media were there, too—and were inundated with the real facts about hemp and marijuana.

Christie, of course, was the outspoken one of the duo, giving frequent interviews and helping coordinate the infant hemp industry. Jack Herer, the arch activist and seminal leader of the movement who died in 2010, recognized her passion and welcomed her outspoken, take-no-prisoners approach to pot politics. Christie, in turn, asked Herer to attend the first Hemp Industries Association (HIA) conference, though he owned no actual company. Herer subsisted pretty much by selling his book at rallies, dealing pot and living very frugally. Christie wanted Herer’s towering presence at the conference to serve as a guiding, moral force as the HIA was formed.

Christie’s swagger and outlaw poise had fascinated me. She was a raconteur who regaled everyone with tales of midnight desert transactions, escapes from law enforcement and stash houses overflowing with bales of Mexican weed.

As much as Herer was the undisputed granddaddy of the legalization movement, he wasn’t on board with the HIA proceedings. Herer was adamant that the HIA’s mission statement include unequivocal support for legalization. He made no distinction between hemp and marijuana. If the DEA outlawed both, why should the activist movement favor one over the other?

Those who disagreed with him believed that the HIA’s purpose was to function as a trade association, first and foremost, facilitating prosperity. Herer accused them of ignoring people behind bars serving time for marijuana “crimes.”

I wrote the story about the conference, which was a huge hit. I also shot my first cover for High Times: Herer wearing his 100 percent hemp suit. The issue sold better than any other in over a decade. Herer had become an icon.

At the HIA conference, Christie’s swagger and outlaw poise had fascinated me. She was a raconteur who regaled everyone with tales of midnight desert transactions, escapes from law enforcement and stash houses overflowing with bales of Mexican weed.

I became friends with Christie and Patrick, and, over the years, they shared their connections, turning me on to a number of stories. They generously allowed me to use their home, located outside of Phoenix in the shadow of the San Tan Mountains, as my base of operations.

Over time I realized that, occasionally, they would move a load of pot in order to fund their legitimate endeavors. I was never part of it, although I wanted to be. I wasn’t looking to be cut in on a deal, but I definitely wanted to photograph the load of weed. But Christie wasn’t having it. When I asked, she’d answer distantly: “Maybe some day…”

But I never stopped asking. And then, during one visit in May 1996, she actually said yes.

It was a Sunday afternoon and tripledigit temperatures had just arrived in the Arizona southland. I climbed into their pickup truck and then spent a few hours with them driving aimlessly from phone booth to phone booth, waiting for the okay to move in and grab the load. I had no idea how the transaction was supposed to occur, but I soon found out.

About 3:30 in the afternoon, Christie and Patrick got the green light. We drove to the outskirts of Phoenix and pulled into a Circle K. Patrick got out and made another phone call, telling the connection that we’d arrived.

This looked dubious. How do you transact a load of pot in the middle of the afternoon in a busy parking lot?

About 15 minutes later, another car pulled in, driven by a fortyish Mexican dude. Patrick got out and walked over to the car. Christie said the driver had family on the other side of the border and they’d been smuggling weed for decades. I watched the conversation progress across the parking lot. The Mexican contact glanced over at me several times—not smiling. After a few minutes, he and Patrick shook hands and he drove off.

Patrick walked back to us and said, “Okay. You can shoot the load, but you gotta drive it.”

“Drive it?” I asked.

“If you want to shoot it, you’re the one taking the risk.”

“How big is it?” I asked.

“One hundred pounds, in bales.”

Now that’s a serious amount of pot. Having 100 pounds in my possession would be a big-time felony. Needless to say, transporting 100 pounds might be somewhat difficult to explain to a cop: “I’m just a journalist covering a story.”

But a centerfold! For a High Times photographer, that’s the Holy Grail—a huge accomplishment in the world of weed. So I said, “OK, let’s do it.”

Patrick handed me a set of car keys and pointed to a nondescript Dodge something or other that had been parked in the Circle K lot all along.

“The weed’s in the trunk,” Pat said. “Now listen. We’re going to drive right behind you the whole way. Drive the speed limit, use your blinkers, put on your seat belt. If you get stopped for any reason, we’ll distract the cops.”

“How?” I asked.

“If you’re pulled over, we’ll drive like complete assholes. We’ll drive onto the shoulder and pass you and the cop on the inside. He’ll probably go after us and leave you alone. If that happens, just drive away slow. We’ll figure something out.”

Now that’s a serious amount of pot. Having 100 pounds in my possession would be a big-time felony. Needless to say, transporting 100 pounds might be somewhat difficult to explain to a cop: “I’m just a journalist covering a story.”

So we set out, driving through countless rural desert communities, with me operating the car as safely as a 16-year-old trying to pass his first driver’s license road test.

About 130 miles later, Patrick passed me. Christie signaled me to follow as they drove by. A couple of minutes later, we pulled into the driveway of a typical Arizona ranch-style home—the stash house. The garage door instantly went up. I pulled the car in and the door closed just as quickly, courtesy of the stash house “manager.”

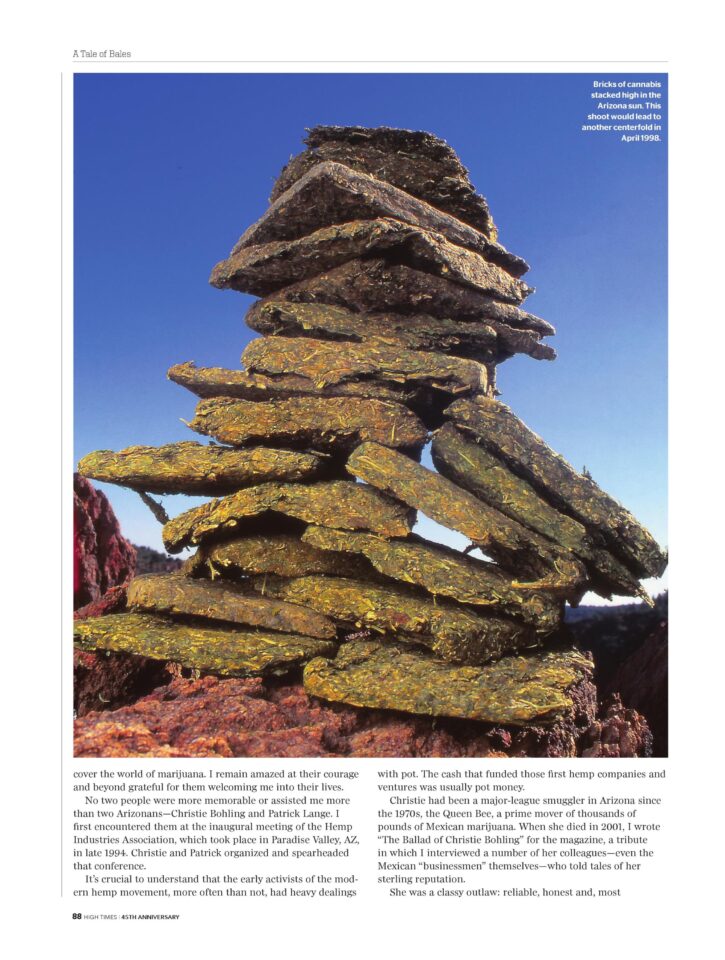

Patrick opened the trunk of the car and pulled out black garbage bags filled with bricks of green Mexican sativa. I was ready. I’d already decided upon a concept. The next available issue was the annual “Travel” issue. I’d brought along a suitcase. We opened it up, stacked the bales and I went to work.

The temperature stood at 114 degrees outdoors. Inside the garage, it was hotter.

In no time, I was a sweaty mess. Stray buds and flakes of green seemed to attach themselves to my slick skin, like I was magnetized. After about 15 minutes, Christie got edgy, but I was immersed in the task. How often do you get to shoot something like this?

“Did you get it yet?” Christie asked.

“Yeah, I think so,” I said, but continued to shoot.

Now, this was before digital cameras. Back then, when you shot on him, you never really knew what you’d get. So, naturally, I wanted to shoot 10 more rolls. I’d momentarily forgotten the risk that all of us were taking.

But Christie was not someone to trifle with. She ended the shoot abruptly: “We’re done.” And so we were.

I put my gear away and went inside the house to wipe the sweat off with wet paper towels and cool off in the AC. Christie and Patrick attended to business inside the garage.

When I came back out, the load had disappeared. So had the car. We smoked a few souvenirs from the shoot and drove off—safely and with a lot less anxiety. As I’d hoped, the shot ran in the “Travel” issue with a big, boastful title: “Pack Your Bags.”

Though pot legalization spreads across the land, I confess that I do miss the adventure and—yes!—the glamour of those early days. I miss the righteous outlaws. Those of us who didn’t grow or deal weed depended on these people for our stash. They were authentic heroes.

Malcolm MacKinnon used the pen name “Dan Skye” during his tenure at High Times.

Read the full issue here.