Acclaimed American poet and novelist Charles Bukowski is known for his writings that challenged the fabric of society as he rose to become a champion of the downtrodden. Beginning with his first collection of poetry, entitled Flower, Fist, and Bestial Wail (1959), he set the tone of his writing career, focusing on the desolation and decline of mankind. Bukowski didn’t publish his first novel until he was 50 years old, Post Office (1971) a semi-autobiographical account of his life as Henry Chinaski, the ultimate antihero and a loose alter ego of himself, a loner.

Chinaski became a recurring character and readers were drawn to Bukowski’s raw truthfulness in his writings. His coming-of-age novel set during the Great Depression, Ham on Rye (1982) was highly acclaimed and featured Chinaski once again. Bukowski was considered a literary outsider with epic talent, but he also had a lesser known stint: a regular contributor to High Times Magazine between 1982-1985, and the story begins with one of the magazine’s first editors.

One of Bukowski’s most controversial works and High Times submission—The Hog—was released as a manuscript, complete with pencil edits by the author, and was bundled with a couple dozen letters written by him to former High Times editor in chief Larry “Ratso” Sloman. While High Times declined to publish it, the manuscript is now worth over $27,000. The letters and manuscript began Sloman and Bukowski’s years-long friendship.

Sloman—nicknamed “Ratso” by Joan Baez—arrived at High Times after a succession crisis took place in late 1978.

“What happened was that Tom Forçade killed himself. Gabrielle Chang, his widow, took over,” former High Times editor in chief Larry Sloman says. “And she had no idea how to run a newspaper, magazine—or whatever. And so she reached out to me, and I had contributed an article to past High Times, and I said OK.”

Sloman had already written for Rolling Stone and Creem, (he later wrote for Heavy Metal and National Lampoon), so he was seasoned with red carpet subjects. He wrote Reefer Madness, a history of pot use in the United States, in 1979, just before his new leadership role with the magazine. William Burroughs wrote the intro in a later edition of the book.

High Times Finds Bukowski

Sloman immediately set out to find the best subjects and writers he could find, including legendary beat poets and rock stars. Sloman says getting Bukowski to write for High Times “was actually my then-girlfriend’s idea.”

Judy, his girlfriend at the time, was a huge Bukowski fan.

“Somehow she got us an address in San Pedro [California],” Sloman says. “And we just went up to the house and knocked on the door. He answered. And I said, ‘I am Larry Sloman of High Times magazine. And I’d like to talk to you about writing [for us] five times.’

“And he goes, ‘Alright, let’s sit out.’ We went in the backyard and sat down, he brought out some wine, of course. We started discussing this. And I said, ‘OK, so look, we don’t have a lot of money…’”

When Sloman approached Bukowski the magazine was under attack—via the U.S. government—during one of many coordinated raids on the paraphernalia industry. High Times lost nearly all of its ad revenue as pipe sellers and others pulled out in a panic. At the time the entire editorial budget was $500. Sloman explained how $400 of the $500 budget went to star writer Ron Rosenbaum, who was the magazine’s go-to weed connoisseur at the time and an esteemed writer and Yale graduate. He wrote a column every month. That left a mere $100 per month for Bukowski.

“So I basically said ‘I could pay you 100 bucks a month for a column.’ And he goes, ‘I don’t care about the money. I’ll do it. Just don’t fuck with my copy—OK?!’ And that was the beginning of a really nice relationship,” Sloman says.

Sloman was expecting something around 400 words or so, but that’s not what happened.

“He started sending me like, novella lengths of work—I mean, literally 2,000-3,000 word articles. It was the greatest bargain we had,” he says.

Sloman explained that The Hog was by far the most offensive and unpublishable piece Bukowski submitted.

With each piece Bukowski sent Sloman, he would write up a cover sheet, and sometimes the word blurbs on the cover sheet wound up as sidebars in the magazine. Their lives further aligned when Sloman became personally involved with mutual friends of Bukowski. One unforgettable memory was attending Bukowski’s wedding to Linda King. Wine was Bukowski’s favorite drug, Sloman says.

“It was in this Thai restaurant, and I’ll never forget because he was being officiated by an occult specialist, I guess she must have known him, but his name was Manley Hall and he wrote many books, but one was called The Secret Teachings of All Ages,” Sloman says. “We went back to the house afterwards, and Bukowski got roaring drunk on wine, as usual, at a reception at the house. At one point he actually starts picking on one of the other guests. Actually, they actually had a fistfight. I have a picture of the two of us right after that fight.”

Bukowski Joins the High Times Family

Just as his column was taking off, High Times also interviewed Bukowski as a subject in 1982. Within that article he describes the childhood experiences that led him to write in the first place.

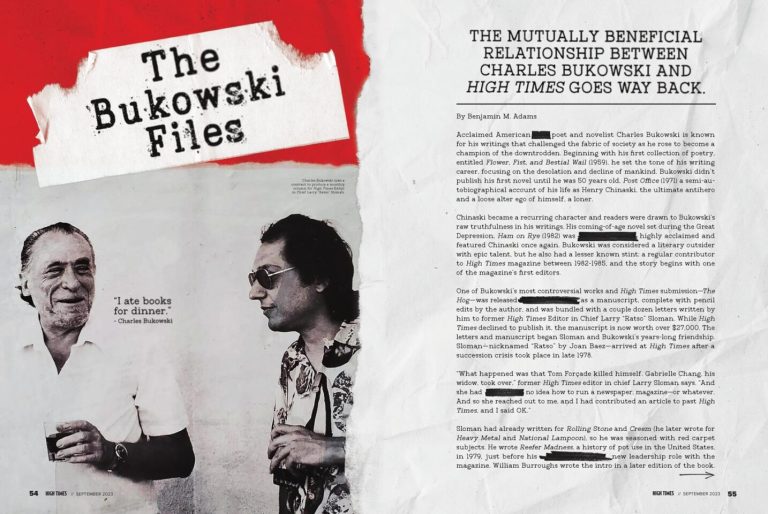

“Between the ages of 15 and 24 I must have read a whole library,” Bukowski told Silvia Bizio for the January 1982 issue. “I ate books for dinner. My father used to say at eight o’clock in the evening: ‘Lights out!’ He had the idea that we had to go to bed early, get up early, and get ahead in the world by doing a good job at whatever you were doing—which is complete bullshit. I knew that, but these books were so much more interesting than my father. In fact, they were the opposite of my father: These books had some heart, had some gamble.

“So when he said, ‘Lights out,’ I would take a little light in my bed, put it under the covers and read, and it would get suffocating under there and hot, but it made each page I turned all the more glorious, like I was taking dope: Sinclair Lewis, Dos Passos, these are my friends under the covers. You don’t know what these guys meant to me; they were strange friends. I was finding under the apparent brutality people that were saying things to me quietly; they were magic people. And now when I read the same guys I think that they weren’t so good.”

In one article entitled Vengeance of the Damned, in the May 1984 issue, Bukowski’s storytelling magic came alive, as he describes an encounter at a department store involving a bum rush of undesirable, deviant low-lifes defying the rules of a capitalist society racked with systemic flaws. An army of hobos dress themselves in luxury while they ignore and mock store clerks and security. After two complicit hobos participated in the apocalyptic store takeover, they relish in delight of being the best-dressed bums in the flophouse that night.

Like High Times Bukowski was an outlaw. In 1968, for instance, the FBI and U.S. Postal Service––Bukowski’s employer at the time—were triggered by the writer’s notes of a column that appeared in the underground Los Angeles paper, Open City, and the FBI put him on a list. Other poets like John Sinclair were also targeted.

High Times History

Bukowski remains one of the most notable contributors to the magazine, but he was far from the only one.

“I had Allen Ginsberg writing for the magazine; William Burroughs was writing for High Times. [Paul] Krassner, Abbie Hoffman, you know—I was getting all these countercultural figures to write,” Sloman says. “The other funny part about my tenure was that I didn’t smoke pot. Because when I was in graduate school years earlier, I got dosed with PCP. And I had a horrible, horrible anxiety attack. So I just wasn’t smoking pot.”

Even though he wasn’t partaking, Sloman was working to legalize marijuana. His journey with High Times led to bigger and better things. Sloman penned two best-selling books for Howard Stern and has released countless other acclaimed works.

While Bukowski was writing for High Times, Sloman produced a music video for Bob Dylan’s song, “Jokerman” (1983). Sloman had previously gone on tour with Dylan in 1975 and knew him well. He recalled one of Dylan’s birthday parties when Dylan got really drunk and sang “Happy Birthday to me!” He also fondly remembers interviewing Yoko Ono in her home in Queens, New York and interviews with Joni Mitchell, and countless others. But despite Sloman’s long list of A-list interviews, Bukowski remains one of his most prized editorial relationships.

Soon after completing his last novel, Pulp, (1994) Bukowski died of leukemia on March 9, 1994, in San Pedro, at age 73. His writings for High Times, however, will live forever.

This article was originally Updated in the September 2023 issue of High Times Magazine.