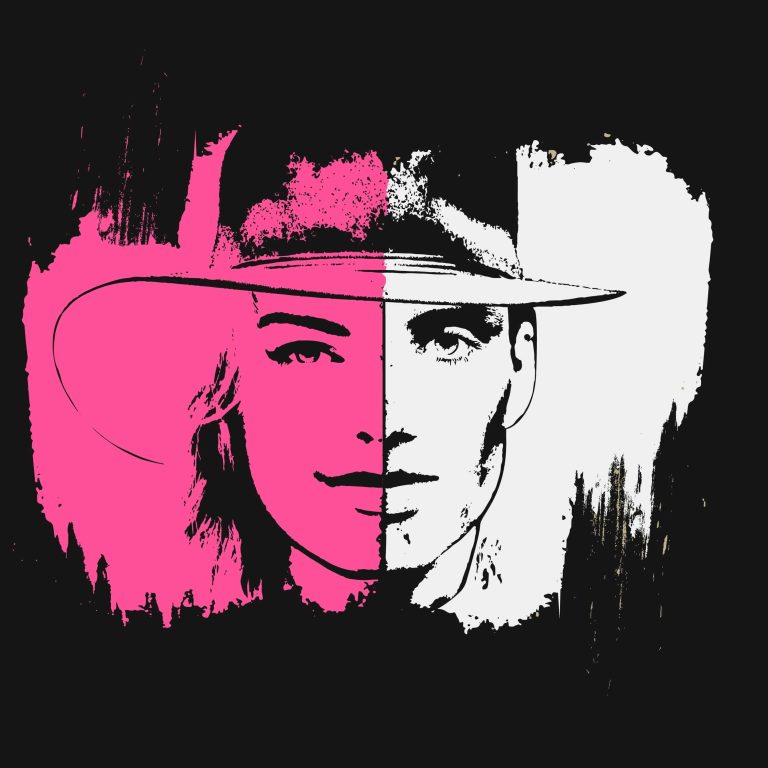

How did Barbenheimer come into existence? Is it because there is something inherently funny about combining a movie as hyperfeminine as Barbie with one as ultramasculine as Oppenheimer? Is it a marketing ploy deployed by a strike-breaking and strike-broken film industry eager to get people back into theaters? Or is it actually just an excuse for dudebros to play with dolls and not feel embarrassed? “I’m just here for the meme,” Ken 1 whispers to Ken 2 when, really, they’re both there for Barbie. And Margot Robbie.

I personally didn’t need an excuse to go see Barbie, which I’d been excited for ever since I learned the film would be written and directed by Greta Gerwig. Gerwig previously made Ladybird, which I really enjoyed, as well as Little Women, which I often tell people I’ve seen when in fact I haven’t, but which I’m sure is also pretty good. I mean, if from here on out we are going to be bombarded with blockbusters based on fetishized consumer products, then the least that Hollywood executives can do is give those blockbusters to filmmakers that genuinely care about their craft. It worked out well for Matt Damon and Ben Affleck’s giant Nike-ad Air, I remember thinking as I bought a ticket, so why shouldn’t it also work for Barbie?

Sadly, I was wrong. What’s worse, I should have known I was wrong. I should have known this when, during one of the more recent trailers for the film, I saw Will Farrell playing a CEO as cartoonishly evil as Ryan Gosling’s Ken was cartoonishly stupid. ‘Barbieland’ is a wildly imaginative set, and the music and choreography are great, too. However, good looks do not make a good movie, and I honestly do not understand how someone as talented as Gerwig – who, for crying out loud, wrote the script together with Marriage Story’s Noah Baumbach – could have put together a narrative as half-baked as this one.

In addition to shallow character writing, Barbie does this thing you also see in Marvel movies and anything starring Dwayne Johnson where cheap jokes are used to hide or justify arbitrary plot points. Maybe Gerwig and Baumbach originally had a better movie in mind, but were ordered to broaden its appeal. Maybe the order came from toy-manufacturer Mattel, which is what Barbie might have just as well been titled.

If Barbie was worse than I expected, Oppenheimer turned out better. I feel confident in saying that this is the best film Christopher Nolan has ever made with the possible exception of Memento. While the premise may not be as original, the screenplay is surprisingly well-written. So well-written, in fact, that you could almost mistake it for the work of Aaron Sorkin. Oppenheimer is basically The Social Network, but for the invention of the atomic bomb instead of Facebook. Nolan has always had a preference for short, snappy scenes. But where The Dark Knight, Dunkirk, and Tenet devoted a good chunk of their run-time to action, Oppenheimer is 3-hours of dialogue, interrupted only by the blast of the infamous Trinity test.

Oppenheimer and his team of scientists stationed at Los Alamos had to test their bombs before they gave Fat Man and Little Boy over to the U.S. government. Washington needed to see if they worked before dropping them on Japan. They also needed to know their blast radius, so they could determine which Japanese cities to bomb. At that point in history, there hadn’t ever been a nuclear explosion, and there was a small yet real possibility that the explosion would set off a chemical chain reaction so large it would destroy not just Hiroshima or Nagasaki, but the entire world. The sequence leading up to the test – the assembling of the bomb, transporting it to the test site, waiting for an ill-timed storm to clear up – is perhaps the most suspenseful of the entire film, and that in spite of the fact that most audience members will already know the outcome. The music, composed by Ludwig Göransson rather than Hans Zimmer, also helps, as does its absence when the bomb goes off.

People will not just be seeing Oppenheimer for Nolan, but also for Cillian Murphy. The actor has had quite the career since he first appeared as the Scarecrow in 2005’s Batman Begins. This is, of course, largely due to his role as gangster Tommy Shelby in the Netflix series Peaky Blinders. Murphy’s Oppenheimer has a lot in common with Tommy, from his suits to his penchant for chain smoking. But the New Mexico desert isn’t interwar Birmingham, and Oppenheimer is not as invincible as the weapons he is making. He’s vulnerable, especially later on in the movie, when he comes to regret his role in the Manhattan Project and is being persecuted by a country intent on expanding its nuclear arsenal, not reducing it. Murphy is joined by Damon, who plays a lieutenant liaising between the scientists and the army that employs them, and a bald Robert Downey, Jr., among other familiar faces. (Gary Oldman is in there, too, but hidden under make-up, so keep an eye out for him).

My brother jokingly suggested taking shrooms before seeing Oppenheimer – a funny but terrifying suggestion as this movie is in many ways scarier than the scariest horror movies. Where the latter are nightmares you can wake up from, Oppenheimer is set in the reality we ourselves live in and can never escape from. The nuclear holocaust that threatens its cast is the same holocaust that threatens us. The mushroom cloud that Oppenheimer observes at Trinity could very well be the last thing that each of us sees before we die. In the last scene of the film, Oppenheimer tells Albert Einstein about the test and how his team was worried about destroying the entire world. “I think we did,” Murphy says, and the screen goes dark.