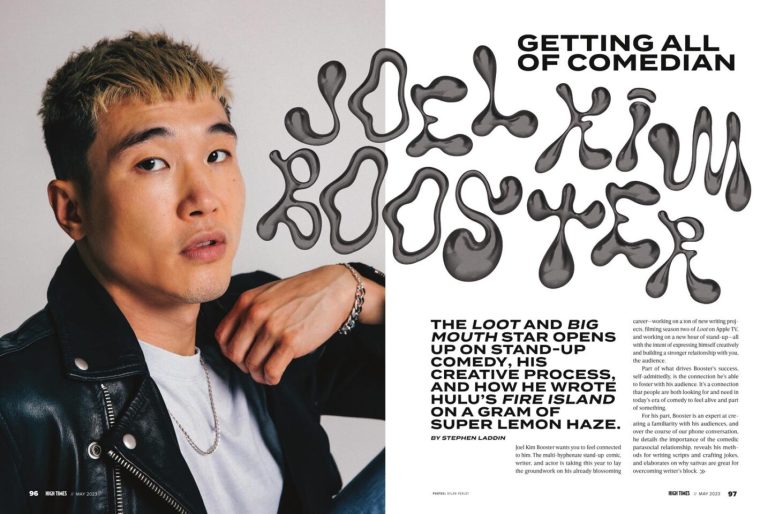

Joel Kim Booster wants you to feel connected to him. The multi-hyphenate stand-up comic, writer, and actor is taking this year to lay the groundwork on his already blossoming career—working on a ton of new writing projects, filming season two of Loot on Apple, and working on a new hour of stand-up—all with the intent of expressing himself creatively and building a stronger relationship with you, the audience.

Part of what drives Booster’s success, self-admittedly, is the connection he’s able to foster with his audience. It’s a connection that people are both looking for and need in today’s era of comedy to feel alive and part of something.

For his part, Booster is an expert at creating a familiarity with his audiences, and over the course of our phone conversation, he details the importance of the comedic parasocial relationship, reveals his methods for writing scripts and crafting jokes, and elaborates on why sativas are great for overcoming writer’s block.

High Times Magazine: Growing up in Illinois, did you always know you wanted to pursue comedy?

Joel Kim Booster: For me, comedy was never something that I felt was open to me. I didn’t think it was an option. I always knew I liked attention from a very young age, and as soon as I knew what performing was, I knew that’s what I wanted to do. Like a lot of kids in the ‘burbs, I was doing school plays and community theater, and that led me to study theater in college. And at that point, I considered myself to be a very serious actor/writer. I wanted to be in serious dramas and write for The Wire someday.

I remember I tried out for the sketch team and the improv team at my college and I didn’t make it into either of them, and that sort of solidified for me that I was just not a funny person.

It wasn’t until I was in Chicago that comedy seemed a little bit accessible. The community is very small there and it’s an amazing place to start stand-up. I was encouraged by Beth Stelling—who I was working on a play with—to try stand-up, and I didn’t realize you could just do it. I remember a theater company had a variety show fundraiser that we were hosting and they had an empty slot and they were like, “Here’s five minutes, do whatever you want.” From that point on, I was sort of hooked on stand-up.

That was the first time I ever thought about doing comedy, and for the next couple of years after, I was pursuing comedy in Chicago mostly as a creative outlet. I never in a million years thought it would turn into anything serious. It just was this fun thing that was just for me that I could flex both my writing muscles and performance muscles at the same time. I never seriously thought anyone would ever take me seriously as a stand-up comic, so I never thought about pursuing it professionally until a couple of years in.

So having “serious” acting aspirations allowed you to approach stand-up with an “I’m just going to have fun with this” attitude.

For sure. And I think because I wasn’t putting pressure on myself to “make it” as a stand-up—especially in the beginning. It was really freeing for me to just sort of play, figure out my voice, experiment a shit ton, and then the pressure came later.

What was the moment when you realized stand-up was actually going to be your main creative vehicle moving forward?

It was when I decided to move to New York. I’d been wearing a lot of different hats in Chicago—writing plays, acting, going on commercial auditions and all of that shit, and performing stand-up. That’s sort of the beauty of Chicago in that it allows you to wear all of those many hats at the same time without having to dedicate yourself to one or the other.

I had visited New York as a stand-up and did one or two shows a night there for a week, and I just fell in love with that energy. I came back to Chicago and three months later moved to New York. When I made the decision to move, I said, “This is the place where stand-up comedy lives. This is the place where stand-up comics become good.” I knew if I wanted to do it and be the best that I could be, New York was the most natural place for me to go.

And was there an ensuing experience that helped validate you’d made the right decision?

It was definitely getting into the Bridgetown Comedy Festival, which is a now defunct comedy festival in Portland, Oregon. I remember it was a pretty hard festival to get into: You had to submit a tape, it had to be a good tape, and it was the first sort of “leveling-up” from being a primarily open-mic comic to being a comic whose name was on a poster. I just felt like a big deal amongst my cohort of comics. The day those emails went out was always a really big day in stand-up comedy in New York, and it was a really gratifying moment to get in.

How do you think your material has evolved—in terms of what inspired you—from your early Chicago days up through the present?

For me, it feels very different, even from just my Comedy Central half-hour to my Netflix special. The place I was writing these jokes from was so different. I was really in the biographical for so long in the beginning—really being focused on me, what was happening to me, what was happening about me—and it was really an exploration of my identity, my background, and how I grew up, which I think is a pretty common place for many stand-up comics to start, regardless of their identity. But for me, it felt especially rich and at the time it felt sort of new and fresh. I don’t necessarily think that’s the case today, but at the time I was starting, nobody was talking about their lives and the intersection of their identities as much as they are now. It definitely felt different back then.

I think now—especially post-Netflix special—the material I’m working on is so all over the map and is goofier and weirder. I have jokes about the Electoral College and I finally have airline jokes [laughs]. It isn’t necessarily all about what it was like being an adopted Korean in a white family—which is always going to be a part of who I am as a person and will therefore exist running in the background of everything I do on stage—but it’s not at the forefront as much as it was at the beginning.

In terms of your more recent projects, you wrote, starred, and executive produced Hulu’s film Fire Island. What went into it creatively and what was the driving force for you to get it made?

I’ve always wanted to make a movie and I felt like I finally had landed on a story that only I could tell in this way, and Pride and Prejudice was sort of the framework for that.

One of my favorite movies to date is Clueless, and I grew up in an era where every teen movie was an adaptation of a Shakespeare play or a classic work of literature. So that’s just in my blood and I think it was a sticky enough sell for my first movie as well.

It’s not easy getting people to pay attention to your work and I think you need certain things—whether it’s a name attached to your movie or, in my case, this hooky adaptation piece. After throwing a million things at the wall, trying to sell a million TV shows, selling a couple of them, developing a million things at once, [Fire Island] was the one that really stuck and stood out amongst everything else I was pitching at the time.

For both scripts and stand-up, what role does cannabis play in those creative journeys?

I’m a firm believer in cannabis. I mean, I’m high right now.

When I have writer’s block, the first thing I do is smoke a joint because it opens up parts of my brain. I have such bad imposter syndrome and such low self-esteem as a writer sometimes that it’s paralyzing. I sit at my computer and I say, “This is stupid, this is dumb.” Every idea—even before it’s able to get out of my body—I judge and critique and it makes it so I’m not writing at all. I find with weed, it really shuts down that voice in a really helpful way for me.

Listen, not everything I’ve ever written on drugs is amazing—it’s actually probably more 50/50. But, I’m able to get it out. Being able to see it in its rawest form is certainly 10 times as helpful as letting it circle around in your brain for a million years while you judge it and try and figure out what’s wrong with it before you even get it on paper.

Any particular strain that helps you sidestep that inner critic?

I’m a sativa guy but I’m not too picky. Within that realm I like to sample as many different strains as possible.

I find sativas very energizing. There’s this idea that weed makes you sluggish and makes you lazy—and I’ve certainly had sluggish and lazy days in my life while I’ve been smoking weed—but I wrote most of Fire Island after a gram of Super Lemon Haze.

Would you say weed is more energizing for you than coffee?

More of a lateral move [compared] to caffeine, which is my number one addiction in life. Sometimes it feels a little bit more like an Adderall. It focuses me, zeroes me in and creates this cone of attention on whatever I’m doing in a moment. It’s not consistent enough to rely on in the day-to-day because—like every other stoner, I go down my Wikipedia rabbit holes—but when it hits right, it hits right and you can get a lot of shit done.

In terms of getting shit done, what would you say has been the driving force behind your success?

I think for me the secret sauce has always been honesty. I think the cornerstone of my act for so long has been the idea of radical transparency and intimacy. And whether or not that’s real, the magic trick of my stand-up is convincing people that they are seeing seven layers deep into my soul and there’s nothing I wouldn’t tell them, nothing I wouldn’t share with them, and nothing I wouldn’t reveal to them. Getting [the audience] invested in that idea has really been the biggest part of my success I think.

Now, are they really seeing seven layers deep? I don’t know. There’s still a lot of stuff that I think is for me and me alone and I’m a very different person off stage than I am on stage. I think the trick of it is to get everyone to think they’re getting all of me.

Does that have a consequence off the stage as well?

For sure. I think that people have a lot of ideas about who I am as a person—how loud I am, how confident I am, how obnoxious I am. I think they’re also disappointed when they meet me in person because I’m not this big, boisterous, fancy gay guy. I’m a pretty lowkey normal dude who is not the star of every interaction—and I don’t want to be, and I don’t think people want me to be.

The other side of that coin too… the number of times I’ve been felt up at meet-and-greets—and I think it’s because I talk about sex with such openness in my set—but the number of times my ass has been grabbed or just uncomfortable touching happens at a meet-and-greet is incalculable at this point. I think people feel comfortable doing that because I am very open about my sex life and I am a very sexual person. I’m open about that on stage and I think that people think that gives them license to do that kind of stuff with me without any consequence.

Does the material in your set make people feel so comfortable with you that they feel comfortable crossing that boundary?

It’s difficult because this is the kind of comedian that I am and I don’t want to shut people out and I don’t want to become a joke robot with no point of view. My point of view will always be rooted in who I am as a person and things that I’ve experienced, and I want that to continue to shine through and be available for people to access. It’s about striking a balance.

This interview was originally Updated in the May 2023 issue of High Times Magazine.