Few names loom as large over exotic American cannabis as Anna Willey. In a legal industry where jokes about quality have become the norm, not many companies have been able to float on top of that noise based on the quality of the product. Hers, California Artisanal Medicine or CAM, is like a battleship ripping through the waves of the decimated California industry.

While many struggle to sell middle-tier products as elite, Willey can barely feed the monster. She’s on the cusp of opening her 2,000-plus-light cathedral of hype in Sacramento, on top of a new facility she just opened in Long Beach. The facility will be her second in California’s capital, with the ground now breaking on a third. Willey jokes she’ll run back to her 500-lighter if she screws it up, but many insiders expect the facility to become one of America’s premier heat factories once it’s finished. Some even inquired with Willey about her helping their own production needs.

But how did a bubbly Indian-born retired software engineer climb to the highest heights of California’s cannabis industry with a stop on the Colorado throne along the way? It all started in what is currently the wildest frontier in legal cannabis, New York City.

Working Your Way Up

Willey arrived in NYC with her parents at the age of 6. At one point, her dad would leave mom in NYC while he headed north to get a degree from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, one of the top engineering schools on the planet. Her mom would become a nurse. By sixth grade in 1985, Willey would become a courier for one of NYC’s famed old-school weed delivery services. She pointed to that moment as where her real cannabis adventure started, but before that, she had enjoyed the smell the first time she was around someone smoking.

“Back then, it was all about the service in New York City,” Willey told High Times. “To get into cannabis, you had to get a job delivering weed, and you needed to kind of work your way up the system.”

When she came home with the cash from her efforts, her parents’ conservative household took a no-questions-asked policy. She would work for the service for a few years. If you ordered cannabis from the service between 2nd and Gold and Murray Hill, Willey would show up right out of school with her Catholic schoolgirl uniform and 1.2 grams for $120 bucks. Willey said it sounds steep, but buyers had to say yes or they would get a visit from a large Puerto Rican man.

Her parents still turned a blind eye.

“I think that they thought it stopped for a little bit in college,” Willey said, smiling. “As all Indian people and children when they’re born, they tell you that you can be many different types of a doctor. You can just pick a type of doctor. So, obviously, I did not want to be a doctor.”

Growing & Coding

Willey noted her sister skipped the medical school plan too, but her mom still tells people she’s a pharmacist. By 10th grade, Willey was bodega hopping in Harlem and the Lower East Side looking for the newest issues of High Times. After graduating from college, Willey would move west to Colorado in 1998.

When she arrived, she immediately met a grower named John from Fort Collins. He offered to set her up in a grow house. There she would learn to grow. She laughed, noting how much easier it is in the modern era to get the info you need, “Nowadays, you just get on to YouTube. And it’s crazy, right?”

When she did get on the internet forums, she felt there was a ton of support. She was amazed by just how many people were open to helping her. With her background in tech, she also didn’t have any fears about covering her tracks as she searched for the answers to her growroom problems on sites that would eventually be shut down by the feds.

Nevertheless, her first round would not go to plan.

“All males,” Willey said. “And I’m talking about ripe ball sacks covering the plant. I kept posting to IC Mag and Overgrow like, ‘These are new strains.’ I thought I created a new strain.”

Willey noted that pollen stuck around for about a year and a half and caused a lot of headaches. The first strains she would work with included DJ Short’s Blueberry and Fort Collins Cough.

Through all this, Willey continued writing code for IBM and Computer Associates. It was the early beginnings of the move towards automation in as many sectors as possible. Willey’s STEM background from childhood through college would give her much more faith in technology than her peers back then. She applied this knowledge to the grow.

“So it was a huge breakthrough, and I was like, ‘Oh my god, I’m breaking through in technology,’ because I was one of the first people to do automated grows,” Willey said. “So everyone that I met would boast about hand watering and [was] also constantly talking about how they want to be there when the lights are on.”

Willey thought the idea of needing to be completely hands-on was dumb, and people needed to learn about timers. What if they got sick or had a flat tire on the way to the grow? There are a thousand reasons to have some redundancy when talking about getting your lights powered up on time.

During that era in Colorado, she would start growing in rockwool. Eventually, she would make the move to Hydroton and use it through 2009 before making the jump to an ebb-and-flow system with Hydroton.

While continuing to develop her skills, she would open Colorado’s third dispensary. Her first fully legal grow would be 30 lights, the next 150. She thought she was in heaven.

The next major factor in her rise came in 2011. She decided she was going to get her general contractor’s license.

“It took me two years. I worked under a bunch of subcontractors, mechanical, plumbing, electrical. l learned enough about those trades to actually get a general contractor license,” Willey said. “And then I was able to do my own builds. That’s when it was over. I had a 40,000-square-foot warehouse. I had 760 lights. I had three warehouses.”

Her weed started to take off. As demand increased, she started the ongoing quest of growing as much fire as possible that she’s on to this day. At the peak of her Colorado cultivation capacity she would have 1,250 lights.

“We would literally do it like New York City deli style,” Willey said. “When we ran out of weed that day, we were out of weed.”

The store would close early every day for three years. Every single day they ran out of weed, even as Willey expanded she just couldn’t keep up. Another thing helping push numbers was the fact hers was the first shop in Colorado offering half-eighths. This allowed people to mix and match more than other dispensaries. When Willey worked the counter herself, the half-eighths weighed a little heavy. The patients loved it.

Moving on from Magic Dust

In 2013 and 2014, she started plotting her move west. She was already getting a lot of her genetics from California.

“I was very aware of how much better California cannabis was; even five months old light deps were severely better than what I call the magic dust,” Willey said.

No matter how good Willey was at growing pot, it was never going to be able to compete with the cannabis being grown at sea level in California. Even to this day, indoor farms skirting the waster in the San Francisco Bay Area are considered among the best in the world.

Willey would eventually sell everything she owned. But as with much of her life, it all started on the forums. They were alive and well through the cannabis floods and droughts of the mid-2010s. As she continued to watch the landscape, it was very obvious to her that those with the heat were in the best shape. California was the land of the heat, and it was before the price crashes we’d start to see later in the decade.

When she arrived in California to start her conquests in 2018, she wanted to get on METRC as soon as possible. Her buildout ended up taking eight months, and everything was on the books. Her friends already here balked at the idea, but her first California runs were basically as compliant as they could be at that moment.

But how did she end up in Sacramento? In her early goings, she would attempt to get set up in Oakland. She quickly realized it was not the most friendly place for cannabis with everyone from the city council to the landlords lining up to milk the industry. But as she worked to fund the California move, one of the jobs she was doing was licensing work. Through that work, she would become familiar with just how friendly Sacramento is to cannabis businesses.

“I noticed it was the number one place that was super friendly to other people. I had a great connection with the Connected team, and Sacramento was celebrating Connected, giving them a store license, whatever they applied for,” Willey said of the observation. “So I was like, ‘OK, this town seems much friendlier.’”

There is an argument to be made that her decision to move to Sacramento has crafted one of the biggest cannabis companies to hit the top-shelf market following legalization. There was always going to be a boutique class of bougie top shelf selection for those who wanted to pay big money. When Willey hit Sacramento, it was the beginning of that kind of quality being normalized for everyone.

She laughed and noted it wasn’t that easy out the gate. When she went all-in on California and sold her last Colorado warehouse, she brought 19 OGs with her that nobody wanted. It was all good though! She found a guy in the desert with a Harvard business degree that would buy all this pot, but he quickly realized consumers couldn’t tell the difference between light deps and indoor, especially if they couldn’t look before they bought it. He ended up making the switch to pounds he could get for $850 as opposed to Willey’s indoor.

“He ditched me for deps in October,” Willey said. “It was brutal and hilarious at the same time.”

Eventually, Willey would get her hands on cuts more suited to Californians’ tastes. As soon as CAM flowers started hitting shelves, it was always priced at least $5 cheaper than things of comparable quality, sometimes even $15 bucks cheaper as others attempted to cash in on whatever hype had gotten them that far. Shelf by shelf, CAM began to dot California from north to south.

One of the reasons for that competitive price point was how much cheaper it was to operate in Sacramento compared to her initial potential home in Oakland.

“I got super lucky with my landlord in Sacramento,” Willey said. “It was still insanely expensive, $1.75 a square foot. But the building was good. We all had a good foundation and relatively good TPO [thermoplastic polyolefin] roofs. They already had some basic power, 800 to 1,000 amps. It had some good bones if you can say that about a building.”

Things were eventually going well. Someone offered to buy her out. But two days before making the deal she pulled out. She was destined to grow the heat for the masses, how could she stop now?

In the end, it would work out.

“Everybody talks about how we got all these investors and whatever. I got lucky and I got one partner and that’s all I really needed. And then one of my closest friends, a grower in Colorado at Grand LAX, Josh Granville, had already come up before, and he was, you know, doing his own thing.”

Easy as Apple Pie

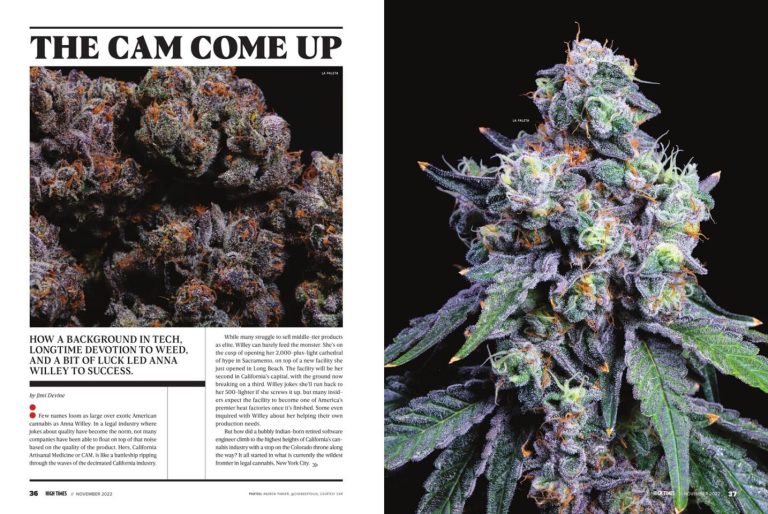

Eventually, Willey got her hands on some Apple Pie. It was some kind of bastardized version of Apple Fritter that her friends at the kings of apple weed, Lumpy’s, had vetted as something close to the original Fritter but not exactly the same thing. This was also the strain that put CAM on my radar back in the day. It was the absolute top of the mountain. There is a strong argument to be made at the peak of apple terps hype a couple of years ago, the three most popular strains were CAM’s Apple Pie, Lumpy’s original Fritter phenos, and Alien Labs’s Atomic Apple. The trio firmly separated themselves from the pack.

She would send a box of that primo Apple Pie to Berner from Cookies. His lineup of dispensaries is now one of CAM’s biggest clients. Willey transitioned to all the doors that have opened for her over the years through her dedication to the flame and regardless of plumbing.

“My experience of being a woman in cannabis is that I’ve just been surrounded by older brothers, mentors, people that have embraced me and shown me so much love and respect,” Willey said. “I’m not here to tell people there is not sexism or misogyny inside the industry. I’m not here to say that. I’m just here to talk about my experience and my experience with all these people that are in cannabis that have moms and sisters and girlfriends, and whatever, like really treated me as such.”

Things would change a lot from those early runs. Gone were the Harvard MBAs that were flush with newly raised capital and ready to buy anything in a jar that tested half decent. Then came the consolidation of many companies. Those with the heat like Willey would be survivors, but it was nuts. She started seeing things like dehydrated nugs going through testing to make the THC numbers higher. She didn’t even realize for a bit you could shop around the same batch for the highest THC numbers since there are no standardized cannabis lab operating procedures (plans are set to change next year.).

“And it’s about to happen. The homogenization of the testing process is going to be revolutionary for cannabis in California. I really do believe that because you will finally be able to grow a lot of strains [that you can’t in a THC-driven market,]” Willey said.

She’s been sitting on cuts for years, waiting for the moment lab testing wouldn’t be as big a factor. About 80% of them are mother plants; the rest are in tissue culture.

We asked Willey if there was a moment where she knew her weed was doing better than most as the walls were caving in on the California industry. She explained it’s not about the hundreds of stores she finds herself in but the sell-through. That’s when she knows she is connecting with the shop’s clientele.

“The one thing I really want to convey is how lucky I am with how much love California has shown some small transplant,” Willey said. “I have the best team. I can’t like, I mean, I want like a whole segment of this conversation to be about how lucky I got.”

This article was originally Updated in the November 2022 issue of High Times Magazine.