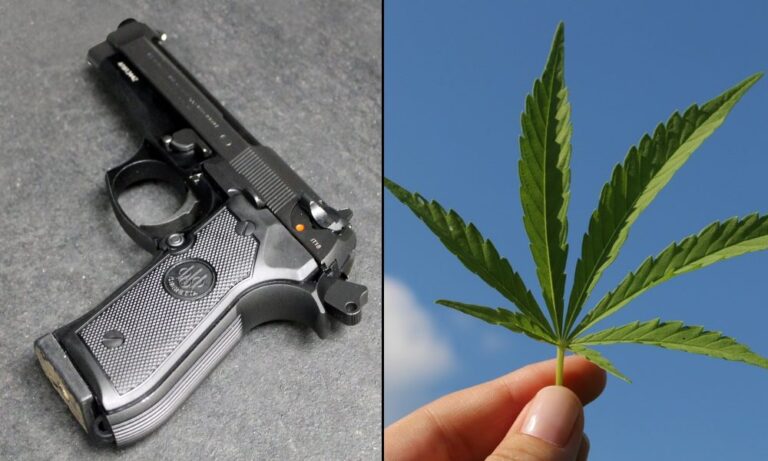

Another federal court has ruled that banning people who use marijuana from possessing firearms is unconstitutional—and it said that the same legal principle also applies to the sale and transfer of guns, too.

The Justice Department has recently found itself in several courts attempting to defend the cannabis firearms ban, and its arguments have faced increased scrutiny in light of broader precedent-setting Second Amendment cases that generally make it more difficult to impose gun restrictions.

Now the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Texas has weighed in, delivering a win to Paola Connelly, an El Paso resident who was convicted of separate charges for possessing and transferring a firearm in 2021 while admitting to being a cannabis consumer.

Judge Kathleen Cardone granted a motion for reconsideration of the case and ultimately dismissed the charges last week.

While the court previously issued the conviction, it said that a more recent ruling in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit warranted a reevaluation. That case relied on U.S. Supreme Court precedent finding that any firearm restrictions must be consistent with the historical context of the Second Amendment’s original 1791 ratification.

The Supreme Court ruling has been central to several challenges against the gun ban for cannabis consumers.

For this latest federal district court case, the Bush-appointed judge disputed the Justice Department’s attempts to assert historical analogues to the marijuana ban, including comparisons to laws against using guns while intoxicated from alcohol and possession by people deemed “unvirtuous.”

Further, the court said that because simple cannabis possession would only rise to a misdemeanor under federal law, “any historical tradition of disarming ‘unlawful’ individuals does not support disarming Connelly for her alleged marijuana use.”

Notably, the judge also cited the fact that President Joe Biden issued a mass pardon last year for people who’ve committed federal marijuana possession offenses.

The ruling states that, “even if Connelly were convicted of simple marijuana possession, that conviction would be expunged by the blanket presidential pardon of all such marijuana possessions that, like Connelly’s, took place before October 6, 2022.”

It should be noted, however, that the president’s clemency action didn’t expunge records; rather the pardons are largely symbolic expressions of formal forgiveness by the federal government. Even so, it speaks to the evolution of federal cannabis policy that seems to be influencing these gun cases.

The court pointed out that DOJ’s defense of the convictions is marred by the fact that the defendant hadn’t actually been convicted of a marijuana offense. She simply admitted to using cannabis for help with sleeping and anxiety.

“The longstanding prohibition on possession of firearms by felons requires the Government to charge and convict an individual before disarming her,” it says.

“Of course, if the Government chooses to prosecute an individual under § 922(g)(3), it will have to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that the individual is an unlawful user of controlled substances. But this process is only afforded ‘to a tiny fraction of those whose rights have been stripped—those that the United States has selected for prosecution and punishment.’ For everyone else—including the millions of individuals who use marijuana in states that have legalized the practice—§ 922(g)(3) categorically prevents them from owning a firearm without a hearing or any preliminary showing from the Government. They must choose to either stop their marijuana use, forgo possession of a firearm, or continue both practices and face up to fifteen years in federal prison.”

“In short, the historical tradition of disarming ‘unlawful’ individuals appears to mainly involve disarming those convicted of serious crimes after they have been afforded criminal process,” the ruling continues. “Section 922(g)(3), in contrast, disarms those who engage in criminal conduct that would give rise to misdemeanor charges, without affording them the procedural protections enshrined in our criminal justice system. The law thus deviates from our Nation’s history of firearm regulation.”

The court went on to challenge the government’s position that cannabis consumers are intrinsically “dangerous,” adding that “over twenty states have legalized the recreational use of marijuana, and millions of U.S. citizens regularly use the substance.”

“It strains credulity to believe that taking part in such a widespread practice can render an individual so dangerous or untrustworthy that they must be stripped of their Second Amendment rights,” Cardone said.

The judge said that the same shortcomings of the government’s defense of upholding the gun possession ban for marijuana consumers are found in the ban on transferring or selling firearms to people who use cannabis.

“The law’s broad prohibition on the sale or transfer of firearms to unlawful users of controlled substances burdens the Second Amendment rights of those individuals to nearly the same extent as § 922(g)(3),” the ruling says. “And, as the Court found when assessing § 922(g)(3), our Nation’s historical tradition of firearm regulation does not support placing such a burden on the Second Amendment right.”

This is one of at least four active federal cases where the government’s marijuana and guns policy is in question.

DOJ recently submitted a brief for one case that originated in Florida and is now before a federal appeals court, involving medical cannabis patients who are contesting the constitutionality of the federal firearms ban.

In that brief, the Justice Department made familiar attempts to draw historical analogues to prior gun laws and also said that allowing medical marijuana patients to have firearms could undermine the government’s ability to restrict such ownership by people who are addicted to controlled substances like fentanyl, cocaine and methamphetamine.

A separate federal court ruled in February that the firearms ban for any cannabis consumer is unconstitutional. The government has since appealed that decision by the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Oklahoma to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit.

Also, DOJ is set to go before the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit in June in another case following a challenge to a federal district court ruling that also concerns firearm possession by a person who admitted to being a cannabis consumer.

Advocates have argued that the fight to end the federal ban for cannabis consumers isn’t about expanding gun rights, per se. Rather, it’s a matter of constitutionality and public safety.

Supporters of the legal challenges have argued that the Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives Bureau (ATF) requirement effectively creates an incentive for cannabis consumers to either lie on the form, buy a gun on the illicit market or simply forgo their right to bear arms.

In 2020, ATF issued an advisory specifically targeting Michigan that requires gun sellers to conduct federal background checks on all unlicensed gun buyers because it said the state’s cannabis laws had enabled “habitual marijuana users” and other disqualified individuals to obtain firearms illegally.

Lawmakers in Congress and state legislatures are also actively looking into gun issues as they related to cannabis policy.

For example, Arkansas legislators recently sent a bill to the governor’s desk that seeks to clarify that medical marijuana patients can obtain concealed carry licenses for firearms.

In light of the federal court’s February ruling on the unconstitutionality of the federal ban, a GOP Pennsylvania senator recently encouraged law enforcement to take steps to remove state barriers to gun ownership for cannabis consumers, focusing on medical marijuana patients.

In Maryland, a key House committee also held a hearing in February on a bill to protect gun rights for medical cannabis patients in the state.

Meanwhile, a GOP congressman filed a bill in January that seeks to allow medical cannabis patients to purchase and possess firearms. The legislation was also introduced in the 116th Congress but was not ultimately enacted.

Read the federal court’s ruling in the Texas marijuana and gun case below: